The California State Assembly advanced a bill Thursday that would extend a controversial road user charge pilot program. File photo

The California State Assembly advanced a bill Thursday that would extend a controversial road user charge pilot program. File photo

STATE — California lawmakers advanced a bill Thursday to extend the state’s slow-moving experiment with a statewide road user charge, advancing a bill reflecting growing concern about the future of the state’s transportation funding.

Authored by Assemblywoman Lori Wilson (D-Suisun City), the bill does not create a mileage fee.

Instead, it extends the state’s pilot program, research efforts, and advisory work until 2035, preserving the option of a per-mile charge to replace declining gas-tax revenues that have funded California’s roads.

The vote was mostly along party lines. No Republicans supported the bill, while Democrats framed the extension as a pragmatic step to address a well-known dilemma: a decline in annual gas tax revenue, electric vehicle adoption and more fuel-efficient vehicles.

“AB 1421 asks a basic fairness question: How do we ensure all motorists pay their fair share, no more and no less?” Wilson told KSEE on Friday. “I am committed to amending AB 1421 in the Senate to explicitly direct the research to help understand and avoid situations where motorists could be double taxed.”

But the EV landscape has dramatically changed over the past five years, according to industry experts and automakers. EV adoption, once projected to surge, has instead slowed, and automakers have pulled back production after taking multibillion-dollar losses. Complicating matters further, the elimination of federal EV tax credits under President Donald Trump removed a key incentive that boosted California’s and the nation’s adoption rates.

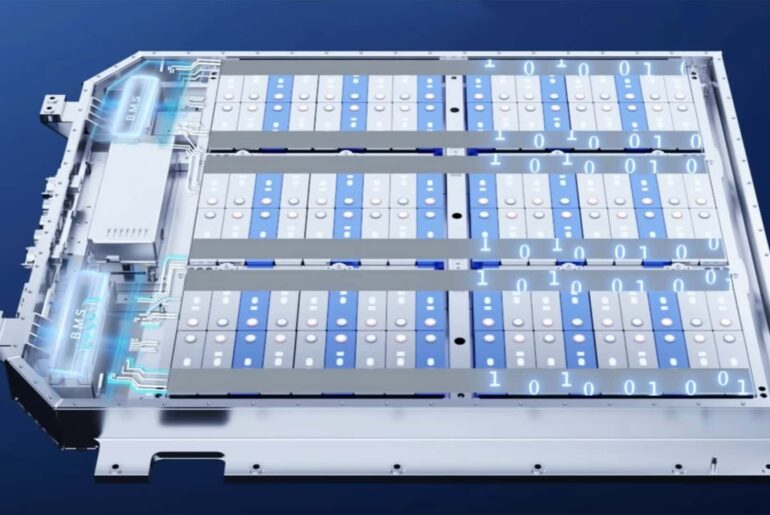

The pilot program, meanwhile, runs through Caltrans and allows volunteers to simulate paying for a per-mile fee.

“When you add up the car tax, the gas tax, and this new mileage tax for a family with two cars, a working family with two parents driving, they would have to pay $4,200 a year to the state of California just for the privilege of driving on crappy roads,” Assemblyman Carl DeMaio (R-San Diego) said.

As lawmakers debate the issue and funding shifts, the RUC is a per-mile fee, the same as the one proposed by SANDAG in its 2021 Regional Transportation Plan. The SANDAG RUC, though, was removed from the plan in 2023 after San Marcos Mayor Rebecca Jones led a contingent of other city leaders, along with public pressure, to abandon the charge.

The state program is only a pilot — a limited opt-in test to gather data. AB 1421 extends the program and requests statewide research. However, the program in 2017 had 5,000 participants and analyzed more than 37 million miles driven.

California began its statewide RUC pilot program in 2014, and lawmakers are seeking to extend it through 2035. Steve Puterski graphic/AI

California began its statewide RUC pilot program in 2014, and lawmakers are seeking to extend it through 2035. Steve Puterski graphic/AI

The pilot tested multiple reporting options, such as odometer reading, plug-in mileage reporting devices, smartphone GPS apps, third-party account managers and non-GPS options. It also tested charging concepts, such as a per-mile rate, a road-type-based fee (state highway or all public roads), and public versus private roads.

“There’s a lot of questions still in terms of how this will play out in an urban area versus a rural area,” Mike Woodman, executive director of the Nevada County Transportation Committee, told KNCO in September 2025. In the end, he said the pilot was “inconclusive.”

Critics say the bill signals the supermajority in the legislature will eventually pass the law. Some have argued the state should rein in spending first, address its growing budget deficit projections, while others, such as DeMaio and others, say the RUC amounts to double taxation, as there is no discussion of an EV-only charge for driving.

Privacy advocates also worry about the state government tracking drivers and the data systems required to execute the RUC.

Supporters, though, say those concerns are premature and emphasized the purpose of the pilot is to understand what will or won’t work.

California’s transportation system is funded largely by gas taxes and fees, which are more than $1.20 per gallon, according to state data and transportation experts. As cars get more fuel-efficient and EVs gain share, gas-tax revenue erodes, prompting the state to launch the RUC pilot in 2014.

The goal has been to identify a stable, long-term revenue stream to backfill gas-tax losses. The Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO had warned for years that with automatic increases to the excise tax, inflation and changing driving habits gas tax’s buying power.

The LAO projected a 64% decline in fuel-tax revenue and 31% in overall transportation revenue, according to AB 1421. According to state records and the Fair Transportation Funding Coalition, fuel taxes generate about $14 billion per year, with $7.8 billion from the gas tax.

“Reducing fuel consumption could mean a projected drop in gas and diesel tax revenues that support road maintenance and public transportation by over $4 billion annually in the next decade,” the ClimatePlan Network said in a release. “Designed properly, the creation of a Road Charge (sic) presents a rare opportunity to rebalance our transportation system and help achieve critical environmental and social goals set by the state. Equity and affordability must also be embedded in the design and implementation of a Road Charge. (sic)”

However, the losses in gas taxes have plateaued over the last two years, according to the state and industry experts.

However, the state RUC program doesn’t separate gas-powered and electric vehicles. In theory, those driving gas-powered vehicles could pay the RUC and gas taxes, while EVs only pay the RUC.

It’s a possible double charge and is the core concern for opponents, and it vexed the San Diego Association of Governments during the regional RUC debate several years ago. While SANDAG executives and the Board of Directors discussed an EV-only RUC, it was never written into the plan.

For years, California led the nation in EV adoption with companies like Tesla exploding and others racing to ramp up production. State leaders predicted accelerating growth and relied on those expectations when passing climate-based legislation and long-range predictions.

But the EV market has radically changed over the past four years, and the picture has shifted:

EVs accounted for 25.3% of new car sales in California in 2023 and early 2024, according to Veloz and the California Energy Commission.

By the end of 2024 and into early 2025, new sales dropped to about 23% based on the 2025 first quarter reports.

In Q2 2025, EVs represented just 21.6% of new car sales, according to E&E News’ analysis of state data.

The California New Car Dealers Association reported EV registrations dropping to just 18.2% in the same period.

“The sales are declining,” Orange County car dealer owner David Simpson told CalMatters. “We’ve filled that gap of people who want those cars — and now they have them — and we’re not seeing a big, huge demand. I don’t see households going 100% EV.”

Analysts say the state has largely captured early adopters, such as tech-savvy, climate-motivated, or higher-income earners willing to navigate changing gaps and higher prices.

The graphic shows the trends in the EV market and how the state’s mandates have been called “unrealistic.” Steve Puterski graphic/AI

The graphic shows the trends in the EV market and how the state’s mandates have been called “unrealistic.” Steve Puterski graphic/AI

Automakers have reacted:

Ford reports more than $16 billion in losses in its EV division since 2022.

Ford has paused development on several EV models.

Toyota leaders call the state’s accelerated timeline “unrealistic.”

Several foreign automakers have reallocated investments into hybrids and rental car companies and are unloading EV fleets due to maintenance and depreciation costs, according to industry reports.

Another headwind is the elimination of federal EV tax credits under President Trump. Those credits offered up to $7,500 for new EVs, $4,000 for used, and up to $40,000 for commercial fleet vehicles, according to reports.

“The question is whether consumers accelerated their purchase timelines to capture expiring benefits,” according to Anthony Puhl of Jato Dynamics, an automotive market research firm. “In other words, did buyers and lessees move forward purchases they were already planning, pulling them into Q3 to take advantage of tax credits and manufacturer discounts before they disappeared? Or is this the start of something more fundamental?”

Industry analysts point to the combination of flat sales, uncertain incentives, and automaker pullbacks as producing a more complex adoption curve, and one less predictable than what California’s regulatory framework assumed.

Fuel-tax forecasts have grown more volatile, making long-term planning more difficult for the state. Each new analysis, from automakers, researchers, or federal agencies, offers different estimates of how quickly drivers will shift away from gas-powered vehicles.

When projects vary wildly year to year, it is more difficult to predict how much revenue California will actually collect. The volatility throws a wrench into long-term infrastructure and road planning and funding, analysts noted.

Some forecasts suggest EV adoption will rebound as prices fall and charging improves, while others suggest California may be entering a slower phase of adoption lasting years.

The state, though, assumes a rapid ascent of adoption and passed the Advanced Clean Cars II program, with the following goals:

Trump, though, rescinded California’s authority to enforce its 100% ZEV and heavy trucks mandate for 2035 when Congress rescinded California’s waiver under the Clean Air Act in 2025. The state had used its waiver to set aggressive climate goals and restrictions on gas-powered vehicles, essentially setting the benchmark for the rest of the country since automakers had to comply to sell in the nation’s largest market.

While California appears on track to miss its 35% target, there is a caveat. Each manufacturer’s sales of 2026 ZEV must be 35% of its total sales averaged for model years 2022-24, CalMatters reported. Only Tesla is on track to meet the 35% mandate.

Manufacturers can be fined $20,000 per noncompliant vehicle or be required to restrict inventory if they miss state targets, EV Magazine reported, which would likely lead to higher prices, Brian Maas, president of the California New Car Dealers Association, told the outlet.

“We’re just not going to make the mandate as presently drafted,” he said. “The most rational is to constrain inventory. The data don’t lie. The demand doesn’t match what the mandate requires.”

Despite a weaker market, state officials say the state is not backing down. Many argue even if EV adoption has decreased, longer-term trends remain in the state’s favor.

Some of those are the 2.5 million ZEVs sold in the state since 2011, and adoption will ramp up with advances in technology and affordability. The state has also built its own incentive program, as Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed a $200 million in EV rebates on Jan. 9 as part of his budget to counteract the federal cuts. CalMatters and others report it may not go into effect until 2027.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Newsom touted ZEV sales in the fourth quarter of 2025 as residents bought 79,066 vehicles. Despite the downward trend, Newsom said the market is resilient and reflects a turning point.

“California didn’t reach 2.5 million (since 2011) zero-emission vehicles by accident — we invested in this future when others said it was impossible,” he said in a statement. “While Washington now cedes the global clean vehicle market to China, California is ensuring American workers and manufacturers can compete and win in the industries that will define this century.”

Even the European Commission is reconsidering its full ZEV transition timeline, according to Wired.

California Air Resources Board officials have said the state remains committed to its 2035 goal, and short-term fluctuations do not change the long-term direction of the global auto industry.

Critics, though, say those statements brush aside the scale of the challenge.

Republican lawmakers argue the state’s mandates are out of step with consumer demand, and EV requirements could raise car prices in an already expensive state. Some warn that EV rules and the RUC, it will lead to a future with higher driving costs.

“Democrats just voted to keep the door open for a mileage tax on drivers,” Assemblywoman Kate Sanchez (R-Rancho Santa Margarita) said. “That means taxing your commute, your kids’ activities, your life. Hard no. Drivers aren’t ATMs.”

Auto dealers have expressed concern that EVs are sitting on lots longer than expected and that pushing manufacturers to accelerate electrification may backfire. Industry analysts say that unless the nation restores some kind of federal incentive structure, California may struggle to sustain the pace its own rules require.

Yes — Tasha Boerner (D-Encinitas), David Alvarez (D-San Diego), Chris Ward (D-San Diego), LaShae Sharp-Collins (D-La Mesa).

No — Carl DeMaio (R-San Diego), Laurie Davies (R-Laguna Niguel)

No vote recorded — Darshana Patel (D-San Diego)

Send story ideas and tips to ncpipeline760@gmail.com. Follow North County Pipeline on Instagram, Facebook, X and Reddit.