New York City’s streets have failed to accommodate a surge of two-wheeled micromobility vehicles — and it’s on Mayor Mamdani to course-correct, according to a group of businesses that make, repair and advocate for electric micromobility in the five boroughs calling itself the “Next-Mile Coalition.”

Mamdani should make it the city’s mission to get New Yorkers out of cars and onto safer, more environmentally friendly two-wheeled vehicles, according to the coalition, which released a 22-page comprehensive list of recommendations for the new mayor on Thursday.

“We developed this report to offer actionable recommendations for how the Mamdani administration can scale micromobility safely and effectively. We’re encouraged by the leadership the administration has already shown and look forward to being thought partners as this work moves forward,” said Melinda Hanson, director at the non-profit E-Mobility Project, and co-chair of the coalition. Other signatories include battery storage firm Popwheels, bike storage purveyor Oonee, refurbish e-bike retailer and e-moped seller Infinite Machine.

The Next Mile Coalition’s vision for the next four years is “a New York where e-bikes and other small electric vehicles are safe, affordable, and integrated into the city’s broader mobility network,” the group said in its report.

Streetsblog readers will recognize the coalition’s recommendations from our coverage of the failures of Mayor Adams’s administration to keep up with the changing streetscape.

The groups called on Mamdani to:

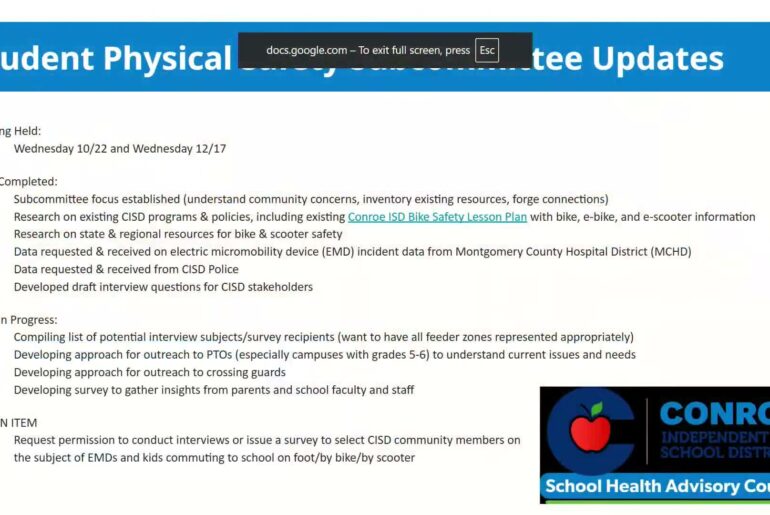

Create an inter-agency task force on micromobility safety

The last time the city put out a comprehensive plan to grow the micromobility movement, and combat the still-raging lithium-ion battery fire crisis, was in March 2023. The Adams administration’s “Charge Safe, Ride Safe” attempted to signal the city’s commitment to expanding the use of micromobility devices, but also that it was taking safety seriously.

But from 2023 to the end of Adams’s term last month, little from the plan was actually done effectively. Deaths and injuries from lithium-ion battery fires have dropped, but the fires themselves continue at alarming levels, according to city stats. The city still lacks a comprehensive network of public, safe, outdoor charging cabinets, and companies that participated in a successful pilot program for such infrastructure are in a holding pattern due to confusing and contradictory FDNY regulations (more on that below).

Now the coalition wants an interagency task force to release a plan that would “identify near term actions, including specific corridors for infrastructure deployment, pilot programs to expand micromobility use in government fleets, and research priorities.”

Private company PopWheels has installed charging sites in Manhattan and Brooklyn, some have been partially funded by Con Edison. Photo: Sophia LebowitzLaunch a battery cabinet certification program

Private company PopWheels has installed charging sites in Manhattan and Brooklyn, some have been partially funded by Con Edison. Photo: Sophia LebowitzLaunch a battery cabinet certification program

Speaking of FDNY regulations and outdoor charging stations, the coalition also called on the city to create a battery cabinet certification program. The current system of battery cabinet certification is not working, they noted: Last year, FDNY required a new test from UL-Solutions, the gold-standard in safe battery testing, that wasn’t yet federally approved — meaning no labs anywhere actually did the test. As a result, the city has not approved any new charging cabinets since early last year.

Recommended

If the administration created its own certification program, companies could build charging cabinets now, without having to worry about federal approval, the report said. The coalition envisions a universe where certified vendors can enjoy fast-tracked approval and expedited “audit-based electrical, fire safety and code review,” which the report said would save companies significant time.

Build at least 100 miles of new protected bike lanes each year

Micromobility users deserve a safe place to use their vehicles — in the form of a rapid expansion of the city’s protected bike lane network, the coalition said.

Streetsblog extensively covered Mayor Adams’s failure to even come close to meeting protected bike lane benchmarks set by the City Council’s 2021 “Streets Master Plan.” But the coalition wants Mamdani to go further, by doubling the previous plan’s goal and building 100 miles of new protected bike lanes per year.

“The biggest priority is removing bottlenecks that slow micromobility infrastructure — from bike lanes to parking and charging,” said coalition co-chair Maxime Renson, Head of US at Upway.

The law tasks DOT with coming up with a new five-year plan this year, which should be released by Dec. 1. The businesses that make up the coalition hope Flynn will incorporate goals for electric micromobility infrastructure into the plan.

Launch a public-facing data dashboard

The coalition suggested an all-in-one-place dashboard for street improvement projects and charging facilities. That one-stop data shop would allow New Yorkers to track the administration’s progress on the “streets master plan” benchmarks.

The City Council last year passed legislation requiring DOT to track its master plan progress in monthly, triannual and annual reports, but the bill did not require a dashboard. DOT also maintains a “current projects” page on its website, but there is no context as to how each project fits in with the larger bike lane and micromobility goals.

A dashboard to display the state of cycling and micromobility infrastructure and traffic crash statistics in the city would help New Yorkers hold the administration accountable to its promises.

Advance legislatively mandated trade-in programs for uncertified batteries

Council Member Oswald Feliz (D-Fordham) passed a bill last year that requires app companies operating in the city to either provide their workers with safe e-bikes, or provide discount codes to e-bike subscription services like Whizz or JOCO. But the coalition’s report charges that the law, which the City Council watered down from Feliz’s original proposal, “has too many loopholes and needs more work to ensure it meets stated objectives.”

Some delivery workers have turned to subscription services to get around, JOCO bikes are Class 1. Photo: Sophia Lebowitz

Some delivery workers have turned to subscription services to get around, JOCO bikes are Class 1. Photo: Sophia Lebowitz

The law states that any “powered” micro mobility device used by a delivery worker on behalf of an app company must meet safety requirements defined by the law, and puts the onus of meeting those requirements on the app company. But the law lets companies out of that mandate by either funding an optional trade-in program, or subsidizing a subscription program for less than 10,000 workers.

The coalition wants Mayor Mamdani to put DOT’s “Department of Sustainable Delivery” in charge of enforcing the law and to refine city rules to make sure it’s achieving its goal of “removing hazardous vehicles and batteries from use and ensuring delivery workers have access to safe, quality equipment.”

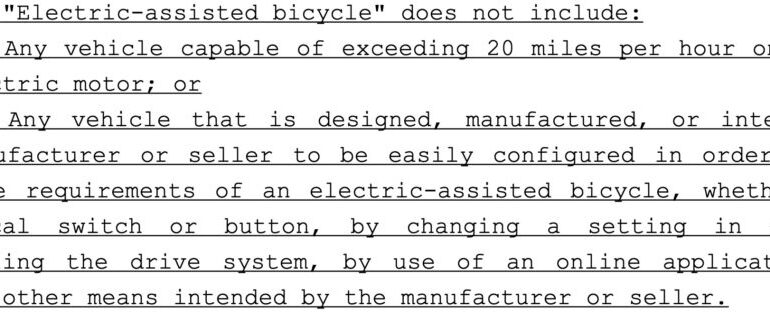

Adopt national standards for e-bike classification

The report calls on Mamdani to push for New York City to adopt the nationally recognized three-class system for e-bikes.

New York City currently uses an e-bike classification system unlike any other city or state in the country. The city’s definition for Class 1 and Class 2 e-bikes follow industry guidelines: Class 1 e-bikes can reach 20 miles per hour with pedal-assist, and Class 2 e-bikes can reach 20 mph with a throttle.

But when it comes to Class 3, New York City goes a different direction. In the Big Apple, Class 3 e-bikes can reach 25 miles per hour with a throttle or pedal assist — 3 mph less than national standards, which also restrict Class 3 e-bikes to pedal-assist operations. This creates confusion for manufacturers trying to sell their products in the city.

A SUPER73 e-bike parked in Lower Manhattan. Photo: Sophia Lebowitz

A SUPER73 e-bike parked in Lower Manhattan. Photo: Sophia Lebowitz

Class 2 e-bikes pose an entirely different challenge. Companies, including Infinite Machine and Upway, will often sell Class 2 bikes with different modes – one for city streets and one for “off-roads” that is significantly faster. These vehicles are known as “e-motos,” and are technically not legal to ride on the street in New York City.

Reps for both Infinite Machine and Upway told Streetsblog they were not opposed to more regulations and that they only sell e-bikes in “Class 2” mode. Technically, after-market modification kits can be used on any e-bike to make them go faster than the legal limit. New Jersey is on track to make it illegal to sell modification kits as part of restrictive e-bike registration legislation awaiting Gov. Phil Murphy’s signature.

Some city lawmakers, however, have embraced a potential ban on Class 3 e-bikes all together. A bill from Council Member Crystal Hudson (D-Brooklyn) would do just that had the support of delivery worker’s rights groups and Transportation Alternatives.