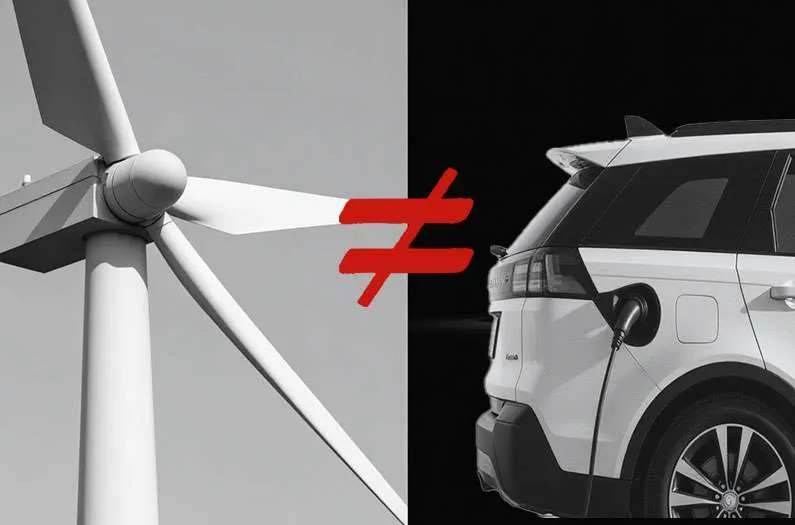

More people in the UK are buying electric vehicles and heat pumps than ever before. But those EVs and heat pumps might not be making a meaningful dent in the UK’s carbon emissions, according to a new analysis.

The UK has focused on electrification as a big part of its decarbonization efforts. But because the UK grid doesn’t get much power from renewable sources, EVs and heat pumps still rely on dirty power from fossil fuels, the study states. Instead, the nation needs to urgently focus on increasing renewable energy generation in addition to expanding nuclear energy and carbon capture.

In other words, argue the researchers, the UK needs to decarbonize its energy supply first and then push electrification. And this argument applies to other countries, says David Dunstan of Queen Mary University of London, who published the analysis in the journal Environmental Research: Energy.

“For all countries, we can safely say that if their average renewable generation is less than their average fossil-fuel generation, they should expand the renewables without any hesitation, and not waste resources on increased electrification,” he says.

What’s at play here is the mix of renewables on a country’s power grid and how easy it is to get that clean energy where and when it’s needed. The variability and intermittency of wind and solar generation have been grossly underestimated in the UK government’s plans to decarbonize British electricity generation, write Dunstan and Alan Drew in their paper. On cloudy or windless days, gaps in supply are still met by gas‑fired power stations.

Meanwhile, when electricity demand is low, there is nowhere for surplus renewable energy to go. Often wind farm owners are paid to shut down turbines because the grid can’t hold all the excess energy.

So in addition to increasing renewable generation, which “is the only effective way we have at present to cut our carbon emissions,” Dunstan says, there is another effort that “really hasn’t been a focus, but needs to be. Introduce technologies that can absorb the large surplus of renewable energy, such as green hydrogen production or synthetic fuel generation.”

The UK government has also talked about expanding nuclear energy and carbon capture and sequestration. “We applaud this but we would rather see serious action rather than just talk,” Dunstan says.

Cost, technological, and policy barriers stand before these steps. For instance, it’s not clear yet whether carbon capture and sequestration could scale up to the extent required. But, says Dunstan, policymakers should concentrate on what is unquestionably needed and feasible, such as nuclear power, grid capacity, and energy storage at the scale required.

“Increasing electrification by encouraging EVs and domestic heat pumps has made zero contribution to cutting our carbon emissions so far,” Dunstan says, “and even in 2030 will be making a much smaller contribution than is claimed, both by government and by the relevant industries and their lobbyists.”

Source: David J Dunstan and Alan Drew. Reappraisal of paths to decarbonising British electricity generation in 2030. Environmental Research: Energy.

Image: ©Anthropocene Magazine