Tesla has quietly crossed a line that could reshape factory work worldwide. On January 21, 2026 the company began mass production of its Optimus Gen 3 humanoid robot at its Fremont plant in California, after several years of prototype testing. Chief executive Elon Musk is targeting up to one million units a year from this site alone, even while warning that early output will be “agonizingly slow” before ramping up.

For people who care about climate and clean industry, this is more than a tech milestone. It is a live experiment in whether physical artificial intelligence can actually help cut emissions instead of simply adding another layer of energy demand.

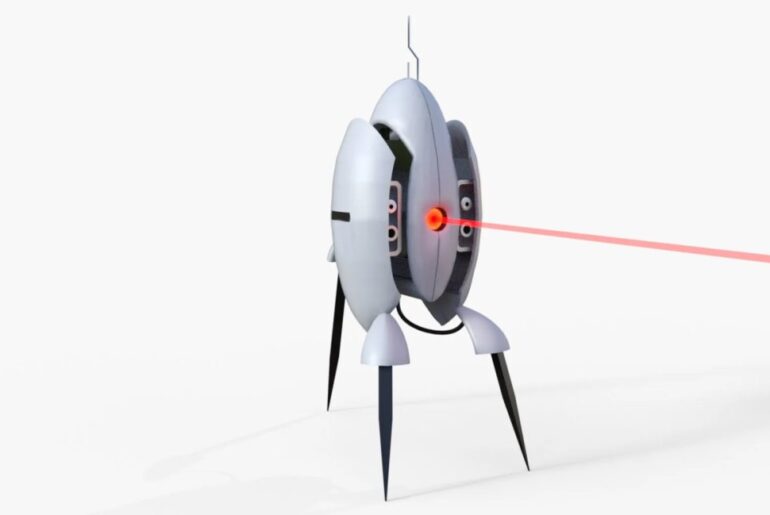

From lab demo to electric co‑worker

Optimus Gen 3 is built as a general purpose factory helper roughly the size and weight of an adult person. Technical briefings describe a robot around 1.70 meters tall and about 57 kilograms in weight, powered by a 2.3 kilowatt-hour battery that can deliver ten to twelve hours of work on a single charge, essentially one full shift.

Each hand has twenty two degrees of freedom driven by tendon-like cables routed through the forearm, which lets Optimus handle everything from small clips to heavier brackets with humanlike finesse. At its core sits a variation of Tesla’s Full Self Driving computer, now repurposed as a robot brain that reads the world through eight cameras, builds a three-dimensional map and learns tasks through simulation and imitation of human workers instead of fixed scripts.

According to coverage of the launch, Tesla engineers say the Gen 3 platform can already perform more than three thousand distinct domestic and industrial tasks, from parts kitting on battery lines to basic inspection and cleaning work.

Musk has floated a long-term production cost in the range of $20,000 to $30,000 per unit, which would put Optimus in the same ballpark as a mid-range electric car and well below the price of many advanced humanoid robots on the market today.

If Tesla hits its own timeline, thousands of these machines could be walking factory aisles by the end of 2026, both in its gigafactories and at early partner sites. That is a lot of robot hands picking up a lot of parts.

Can millions of humanoid robots really be good for the climate

From a climate perspective the answer depends on two things, the electricity that feeds these robots and the way they are actually used. Research on industrial automation shows that robots can improve energy efficiency by running processes more smoothly, reducing scrap and enabling more precise control, which lowers emissions per unit of output.

Several recent studies in manufacturing economies have found that robot adoption can cut energy intensity and help drive greener technologies when the wider system is designed with efficiency in mind.

YouTube: @Tesla

At the same time, each robot is a serious electricity user. Analyses of traditional industrial robots suggest annual consumption on the order of tens of thousands of kilowatt hours per unit when they operate many hours a day, with one estimate putting a typical industrial robot near 21,000 kilowatt hours per year.

Multiply that by the kind of fleet Musk talks about and you end up with terawatt hours of extra demand over the robots’ lifetimes. That is the kind of load that shows up on a national electric bill.

If that power comes mostly from renewables, the overall impact can still be positive, especially if Optimus helps speed up production of electric vehicles, batteries and solar equipment. If the electricity comes from coal and gas, the climate math looks far less friendly.

Tesla argues that its gigafactories are designed to run on sustainable energy and has long promoted large solar arrays and other clean power at sites like Gigafactory Nevada, which has been presented as an all-electric facility aiming for 100% renewable supply.

In its latest Impact Report the company says customers avoided nearly 32 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2024 through the use of its vehicles and energy products. If the same level of transparency and ambition is applied to the Optimus program, humanoid robots could slot into a genuinely cleaner industrial ecosystem rather than becoming a new source of hidden emissions.

Workers, safety and a just transition

There is also a human side to this story that does not show up in glossy robot demo videos. Tesla’s own description of Optimus focuses on “unsafe, repetitive and boring” tasks, the kind of work that can involve heavy lifting, exposure to chemicals or endless hours on the same station.

Handing those jobs to a battery-powered machine can reduce injuries and free people for more skilled roles, at least in theory. Anyone who has worked a night shift on a noisy line knows how appealing that sounds.

Unions are already signalling the risks if that theory does not hold. In South Korea, Hyundai Motor’s union has warned that the group’s own humanoid robot rollout with Boston Dynamics Atlas could bring “employment shocks” and insists that no new robots should enter plants without a labor management agreement. Those concerns will echo across the sector as humanoids appear in battery plants, logistics centers and recycling facilities.

For green policy makers, that means robot adoption has to travel alongside just transition plans, safety standards and real dialogue with workers. A low-carbon factory that leaves communities behind is not truly sustainable.

A fast-moving race in humanoid robotics

Tesla is stepping into a crowded and accelerating field. Hyundai backed Boston Dynamics plans to mass produce its Atlas humanoid by 2028 with a dedicated factory capable of about 30,000 units a year, starting at a new electric vehicle plant in Georgia. Figure AI and several Chinese manufacturers are also racing to deploy humanoids in warehouses and assembly lines, often pairing them with powerful AI models from players like Google DeepMind.

For the environment, that competition cuts both ways. On one side, standardized humanoid robots could help retrofit existing factories with smarter automation that saves energy and reduces waste, without tearing down and rebuilding entire plants.

On the other, the sheer scale of production Musk sketches out, from a one-million-unit line in Fremont to plans for much larger capacity in Texas, implies a vast new layer of mining, chip fabrication and electricity use that only makes sense in a world racing toward clean power and robust recycling.

In that sense, the Optimus Gen 3 launch is not just a curiosity for robotics fans. It is an early glimpse of how physical artificial intelligence might weave itself into the climate story, for better or for worse. Whether these robots help deliver a low-carbon “age of abundance” or simply shift emissions from one corner of the economy to another will depend on choices made now about energy, materials and labor.

The press release was published by TokenRing AI.