Some questions are impossible to answer. Where did we come from? What’s the meaning of life? What happens after we die? Does anyone who owns a plug-in hybrid vehicle actually charge their car?

While most of those questions have baffled philosophers for centuries, that last one has really only bothered people in the past three to four years. The U.S. government has no reporting requirements when it comes to PHEV charging usage, and many automakers choose not to disclose the data. Some claim not to track it at all. So gathering any real knowledge on the subject is tough—unless you live in Europe.

![]()

![]()

A study published last year by the European Commission examined the fuel consumption of roughly 600,000 vehicles in Europe throughout 2021, which included gasoline-, diesel-, and hybrid-powered vehicles. The organization was able to do this because every car built after December 2020 has been required to have an on-board fuel consumption monitoring (OBFCM) device installed by the manufacturer. This device, as you’ve probably guessed, monitors real-world fuel consumption and relays that info back to the manufacturers, whether remotely or during routine dealership service.

The Reality Of Plug-Ins

The results painted a picture many suspected: Drivers of plug-in hybrids weren’t charging often enough to take advantage of their electric propulsion. The study found that plug-ins were consuming about 3.5 times more fuel than what was predicted via Europe’s Worldwide harmonized Light vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP) values, the European equivalent of our EPA numbers. The chart below gives you a sense of what the real-world versus WLTP numbers should be, showing the same test results for normal gas- and diesel-powered cars.

The gaps here are pretty insane. Source: European Commission

The gaps here are pretty insane. Source: European Commission

In its analysis, the European Commission calls out the obvious: People just weren’t charging as much as the WLTP numbers expected them to:

The analysis of the real-world data confirms that the real-world gap for plug-in hybrids is significantly higher than for conventional vehicles. A major reason for such a discrepancy is the mismatch between the utility factor used during type-approval and the actual vehicle charging and driving patterns.

Nailing down these figures for American plug-in fuel economy is tougher because there is no such standardized tracking method, and no government entity publishes data from manufacturers. So I reached out to every automaker that currently sells a PHEV in America in search of answers. Specifically, I wanted to know whether their buyers actually charge their vehicle via the charging port, or if they just treat it as a gas car without ever stopping to top up on electrons.

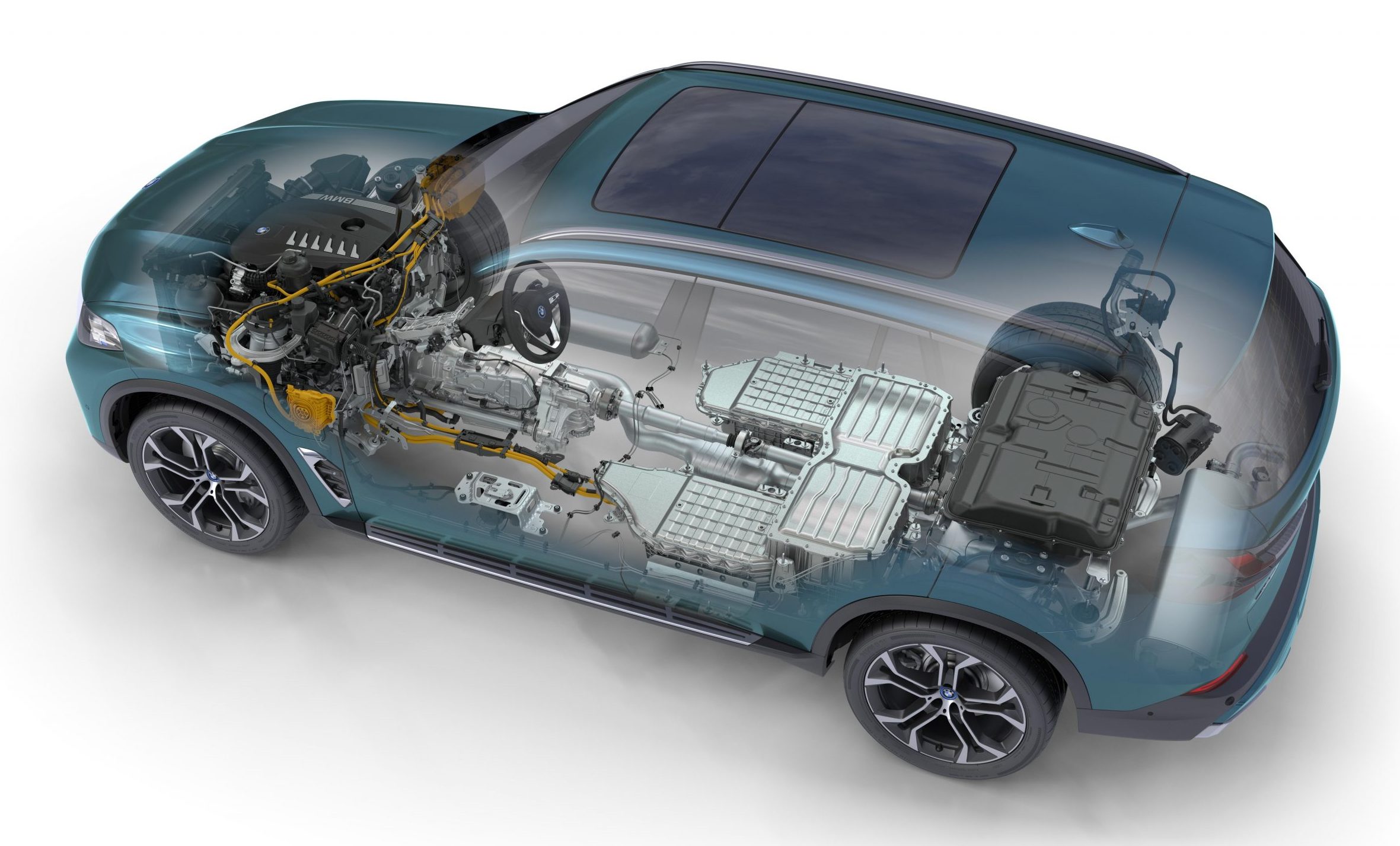

Most Automakers Didn’t Want To Share BMW’s Gen5 plug-in hybrid architecture, shown in the current X5. Source: BMW

BMW’s Gen5 plug-in hybrid architecture, shown in the current X5. Source: BMW

An Audi spokesperson told me the company doesn’t track the data. Bentley told me it was “not able to support these questions,” while Land Rover said “we do not have this level of information to share.” Mitsubishi and Volvo said they’re looking into whether they can provide any data. Ford declined to comment. Stellantis told me it doesn’t share customer usage and behavior data. Ferrari did not respond to my inquiry. Not a great start.

BMW sent over some interesting data, though. While the company didn’t specify the percentage of PHEV owners who charge their cars versus those who don’t, the numbers suggest most people are actually using the charging port. From a spokesperson:

BMW PHEV customers charge very frequently: 15% charge at least once per day, 52% at least 2-4 times per week.

On average across all our PHEV customers we do see that they charge 0.7x per day.

>95% of all PHEV charging sessions are non-public (=home)

Kia sent over even more data. The company recently surveyed nearly 1000 EV and PHEV owners to find out more about its customers’ charging habits. Here’s what it found:

At-Home Charging:

97% of Kia PHEV and EV, owners charge predominantly at home. A majority of Kia EV owners have Level 2 chargers, while the majority of Kia PHEV Owners use Level 1 (wall outlet) at home. On-average, PHEV owners typically charge for 6.5 hours and the EV owners typically charge for 6.6 hours.

At-Work and Public Charging:

Of the Kia EV and PHEV owners, only 5% of PHEV owners and 8% of EV owners charge their vehicles at work. Roughly 6% of PHEV owners and 16% of EV owners routinely use public chargers. Our engineers have concluded that the large majority of these owners live in areas that do not provide at-home charging, such as an apartment complex or a home that does not have Level 2 charging.

At-Home vs At-Work Charging:

When looking at the ratio of at-home vs public and at-work charging, close to 80% of EV charging is done at home, and that number is close to 90% for PHEV owners.

That bit about PHEV owners using a wall charger makes a lot of sense, and seems to line up with BMW’s data. Most plug-in hybrids have relatively small batteries, which means they don’t need Level 2 chargers to go from empty to full overnight. The point about just 6% of PHEV owners using public chargers isn’t a surprise, either. There’s no reason to stop for a juice-up on your tiny battery when you have a whole gas engine as a backup to get you home. So the people hitting public chargers just for their PHEV likely have no other place to juice up.

Source: Kia

Source: Kia

A Kia representative went on to tell me that 92.8% of PHEV owners do charge their vehicles, which means 7.2% do not. This is survey data, so it’s not as reliable as direct monitoring, but it’s better than nothing.

Hyundai’s PHEV owners charge even more, according to the company. It took a survey that sampled the charging habits of 311 PHEV owners, which, according to a representative, were mostly Tucson PHEV drivers. Here’s what it found:

Nearly everyone (99%) stated they charge their vehicles. A full half charge once or more per day, while nearly 40% charge several times a week. During charging sessions nearly all owners are charging their PHEVs back to full charge.

71% of PHEV’s with longer commutes (30+ miles) stated they charge once a day or more, suggesting they are trying to take as much advantage of their time in EV mode as possible.

PHEV owners with shorter commutes (under 20 miles) reported less frequent daily charging and more likely weekly charging.

What Does It All Mean? Source: Jeep

Source: Jeep

The Hyundai data, combined with those Kia figures and BMW’s statistics, mean we’re on a path to finding out whether most people actually charge their PHEVs. But without data from bigger brands like Stellantis, Volvo, Ford, and Audi, it’s impossible to give a definitive answer. Buyers of different brands have different habits, so what’s true for Hyundai might not be true for brands like Jeep or Alfa Romeo. Still, the results are telling. There’s a lot of speculation that most PHEV drivers never charge their vehicles, but that doesn’t seem to be the case for BMW, Kia, and Hyundai drivers.

Logically, you’d think people would take advantage of their car’s battery propulsion whenever possible. Why pay extra for the plug-in hybrid powertrain if you’re not going to use it? That’s doubly true if you have access to a garage or a driveway with a wall plug. All you have to do is pop in the charger when you get home every day. And if you’re buying a PHEV, that’s probably your plan from the start.

With PHEVs becoming more numerous, I hope data like this will become more readily available. From what these numbers suggest, people might actually be catching on.

[Ed Note: The important thing, here, is not how many times someone charges, or what percentage of owners charge at all — what matters is the percentage of total miles traveled that are done in electric mode vs ICE mode. Per-mileage traveled is key. One of the big challenges with PHEVs is that automakers are rewarded credits by governments based on an assumed usage, and if that usage in the real world is actually more ICE than was assumed, then PHEVs can begin to seem like a workaround for automakers who don’t want to invest in cleaner technology — a workaround that doesn’t yield the environmental benefits lawmakers deem necessary to keep Americans/the earth healthy. It’s also worth noting that European drivers are very different than American drivers, and small-car drivers are much different than pickup truck drivers (a pickup truck driver, for example, might have more of an incentive to plug in for their commute due to their poor ICE fuel economy). In addition, it’s worth noting that PHEVs in the U.S. are simply not good enough, and data suggests that if they improve (i.e. they offer more of an EV range, like EREVs should) then we’ll likely see more miles traveled using EV propulsion than ICE propulsion. Check out reporting by John Voelcker on this topic. Though he and I disagree on the environmental value of EREVs (I think they’ll be a huge boon for many reasons enumerated here), he’s sharp and has spent far too many hours looking into this very topic. -DT].

Top graphic images: Hyundai

Support our mission of championing car culture by becoming an Official Autopian Member.